Mexico’s Democracy, on the Path to Autocratization?

Gonzalo Meza

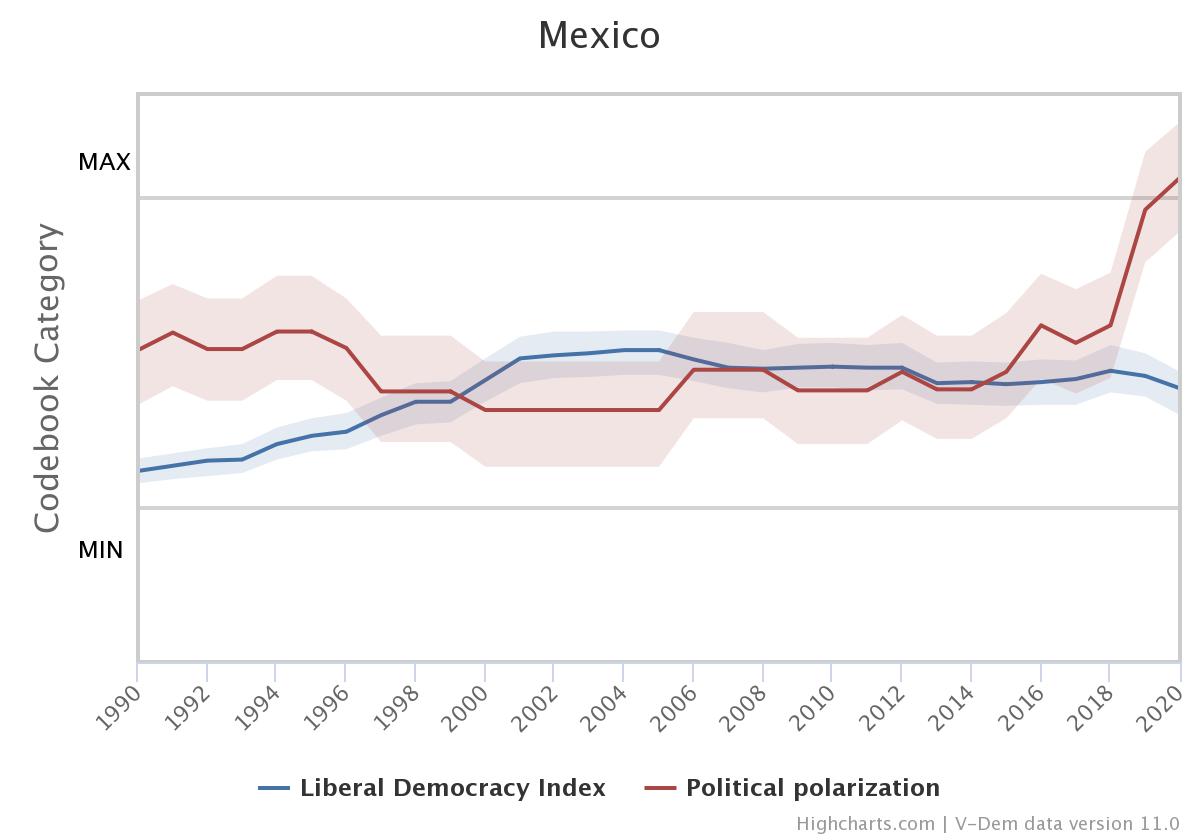

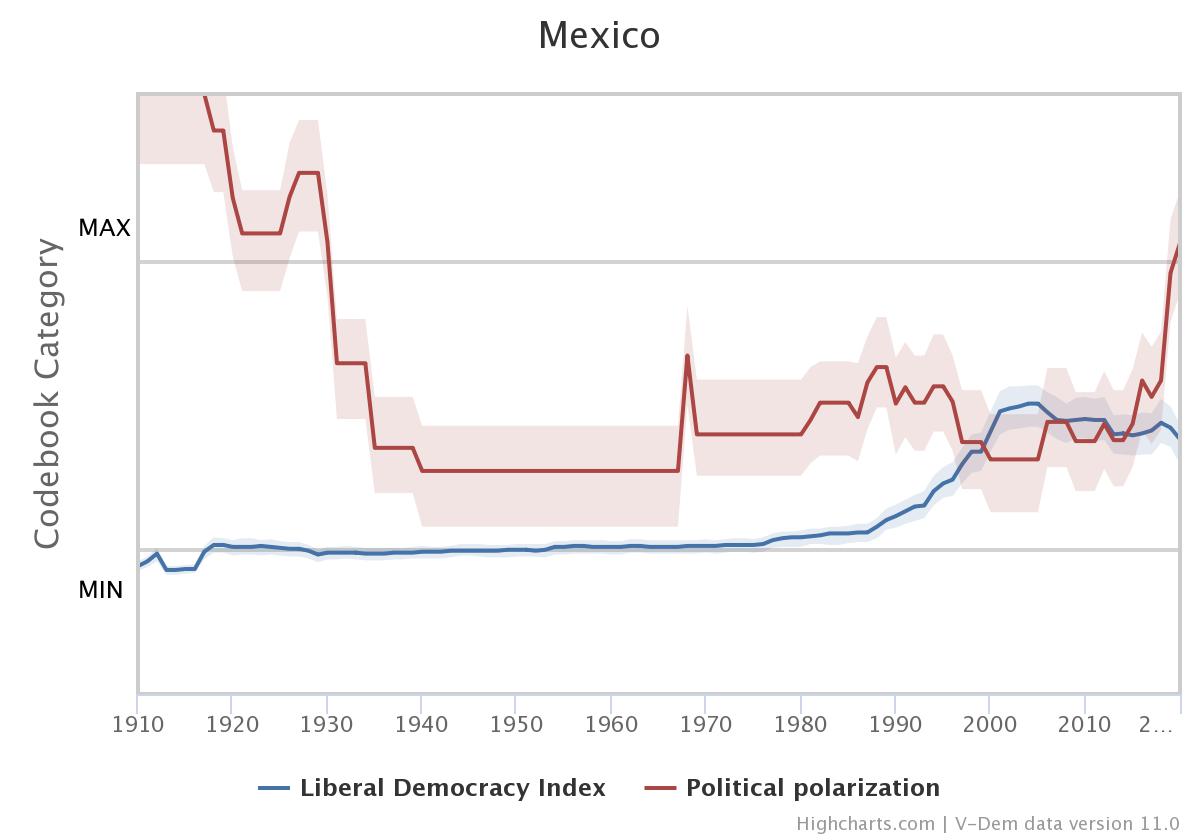

In 2018, the left-wing candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), from the newly founded National Regeneration Movement, Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional, MORENA, won the Mexican presidency with over 53% of the votes (National Electoral Institute, INE 2018). Thanks to a political coalition, AMLO obtained majorities in the Mexican Congress and the Senate. Analysts regarded these elections as another important step of Mexican democratic consolidation, which started in 2000 when the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) lost the presidency for the first time in 70 years. The party’s switching presented a picture of a strong democracy where political actors could participate in free and transparent elections organized by an independent electoral institute, INE, that proved effective and credible. However, the first half of AMLO’s six-year term tells us a different story. During his mandate, he has claimed himself as a legitimate instrument to channel the people’s will. All his political discourses and speeches from the moment he was a candidate until now are constructed upon the narrative: the good people (“el pueblo bueno”) vs. the elite, which he labels as “mafia in power, the corrupt, the neoliberal technocrats.” His populist form of government, based on wits and whims, has provoked a democratic backsliding in the country. According to V-Dem –which presents the scores for liberal democracies (LDI)– Mexico went down from 0.45 in 2018 to 0.41 in 2020. Besides, political polarization in the country increased dramatically from -0.03 in 2018 to 1.62 in 2020, reaching the highest levels that the country has experienced since 1930 (See graphics). Is Mexico’s democracy on the route to autocratization?

AMLO is a populist. Populism is “a political strategy through which a personalistic leader seeks or exercises government power based on direct, unmediated, institutionalized support from followers” (Weyland 2020, 408). It is an ideology that considers society separated in two antagonistic groups, “the people” vs. “the elite.” (Pevehouse, 2020). Populists are anti-elite antipluralists. When running for office, they portray their political competitors as immoral and corrupt. AMLO is a populist with no adjectives (right or left). However, he considers himself as belonging to the left. AMLO is anti-elite and antipluralist. Those who disagree with him are labeled as “conservatives –from the right– corrupt, immoral, and sold to the interests of the powerful,” which includes a good number of prestigious journalists and media corporations against whom he rants constantly. Part of his questionable decisions included the termination of contracts to construct an airport in Texcoco, close to Mexico City. In 2000, the current and busiest airport, located in the capital, surpassed its maximum operations capacity. Revoking the operation costed millions of dollars, more than needed to finish it. Instead, AMLO decided to reshape a military airport in a different location, in Santa Lucía, far from Mexico City and not easily accessible. One of the arguments to cancel the construction of the new airport was its impact on the environment. Although independent agencies validated this argument, AMLO has not been consistent in his environmental policies. For instance, he decided to construct a 948-mile intercity touristic train to traverse the Yucatán Peninsula, the “Maya Train.” The purpose of the train is to boost tourism and economic development in the area. However, many environmental and indigenous groups have complained that the train will considerably impact the region’s ecosystem. Other examples of AMLO’s inconsistencies to protect the environment are the significant resources he has invested in the construction of a refinery and energy production based on hydrocarbons. Mexico has not developed clear and long-term plans for the research and development of clean energy production. Mexican analysts evidenced this fact during the COP 26 in Glasgow.

Is AMLO a threat to democracy?

Populism is a threat to democracy because a democracy relies on strong firm institutions that prevent the abuse of power and protect individual liberties through several institutions independent of political personalities or parties (Müller, 2016). During his administration, AMLO has tried to centralize power in the executive and has challenged the norms and institutions of the young and unstable Mexican democratic system. He does so especially during the “mañaneras,” the morning “press conferences” that he gives in the National Palace every day. Las “mañaneras” are a privileged way for AMLO to criticize ideas, people and challenge institutions that he disagrees with him. They are broadcast and live stream nationwide through public channels. In his “mañaneras,” he has ranted against the National Electoral Institute (INE), in charge of elections, saying it is costly and inefficient (Sánchez and Green, 2021): “There can be no rich INE and poor people.” He has also criticized the Mexican Courts and pressed the Supreme Court to go along with his plans. An example is the “Zaldívar Law.” Arturo Fernando Zaldívar is the Chief Justice, whose term ends by law in Dec. 2022. Part of his functions includes being the President of the Federal Judiciary Council, the governing body of Mexico’s judicial system. Zaldívar has ruled in favor of AMLO in many controversial decisions, for example, a referendum on whether the former Mexican Presidents should be investigated for corruption. As part of the constitutional reforms to the Judiciary, Mexican Congress approved in April an extension to the term of the Chief Justice (“Zaldívar Law”). Nevertheless, Zaldívar said in August that he would not stay for another term. Indeed, in November 2021, the Supreme Court invalidated the extension of Zaldívar, saying it was against the constitution. There is a reason why AMLO desires to get more control of the Judiciary. As of Nov. 2021, his party MORENA does not have 2/3 of both Cameras to change the constitution.

Can AMLO provoke a reversion to an autocracy?

The erosion of democracy can have different impacts, depending on the type of democracies. The term backsliding embraces multiple processes and agents, and it can take us to different endpoints at different speeds. Populists work to dismantle democratic institutions, but to be successful, two conditions are necessary at the same time: severe institutional weaknesses and severe economic crises –or a considerable resource windfall, generally hydrocarbons– (Weyland, 2020). Another essential component to dismantle liberal democracies is severe polarization. A reversion to autocracy in Mexico at this point is not likely.

First, the federal political institutions (not at the municipal level) have proven to be resilient. This resilience was built over the years. The transition to democracy started in 1977 and was possible due to changes in government rules and practices. The political reforms created a social and political awareness of the importance of transparency and accountability in government and elections. Moreover, since 2000 several new political institutions have strengthened democracy by fighting against electoral and government malpractices, ineffectiveness, and corruption. Some of them include the creation in 2002 of the law to access public information and the Career professionalization system in 2003, which allows people the chance to get into government positions based on their merit.

Second, since the Mexican crisis of the Peso in 1994, economic institutions, primarily Banco de México (BANXICO “Mexico’s Federal Reserve”), have put a set of mechanisms to shield the economy against external and internal economic impacts. Having learned from the previous crisis, Mexico has built solid macroeconomic institutions. The country is more resilient to international and domestic shocks than before. It does not mean that Mexico has performed well economically. Between 1980 and 2018, the economic growth on average was 2% a year. Besides, the country has not been able to fight efficiently against the reduction of poverty and the tremendous disparities in income. The pandemic has hit the country tremendously, leaving thousands of people unemployed, and there are very few signs of economic recovery. Moreover, despite his many promises, AMLO’s administration has not been able to control violence in the country. During his 3-year administration, the country has registered more than 100,000 violent deaths, a higher number than in previous administrations. The drug kingpins control many municipalities, especially in Michoacán and the State has no strategy to curb criminals, except “Abrazos no balazos” (Hugs, not bullets), said AMLO. Although AMLO’s approval ratings as of Nov. 2021 are still very high, above 60%, people have deeply felt the impact of the economic and security crisis in their lives. During the mid-term elections, MORENA and its coalition lost congressional supermajority. They slipped from a 2/3 majority in the lower house to a simple majority (279/500). Of the 15 states that contended for governor during these elections, MORENA obtained 11 states. Currently, this party rules in half of the 32 states in Mexico.

Third. Severe polarization can be a danger for democracies and societies. Extreme polarization undermines democracies and societies in several different ways. One of its dangerous consequences is radical divisions, which impede reaching consensus among actors in various settings. The components of societal cohesion are destroyed, and invisible walls are constructed among neighbors, people who share the same space, community, territory, or nation. Dialogue is replaced by monologues where the reality is presented in a caricatural way as “us versus them,” black and white, liberal vs. conservative, democrats vs. republicans (McCoy et al., 2018). At early stages, before polarization has progressed, oppositions have much institutional leverage “in the form of horizontal accountability mechanisms –Judiciaries, legislatures, bureaucracies, as well as vertical and societal mobilizational capacity from organized political and civil societies” (Somer et al. 2021). Although Mexico is in an early stage of polarization, some strategies are being taken to counteract polarization. Mass Media and civic society have become powerful anti-establishment actors who have denounced AMLO’s attacks against free media time and again. Despite AMLO’s attacks against the Judiciary and the INE, those institutions have proven to be resilient. Although federal political institutions are not the most efficient ones, they have acted as powerful barriers and shields of Mexican democracy. Federal institutions and political actors have become a powerful anti-establishment and have served to counter democratic backsliding in Mexico.

Conclusion

AMLO has provoked a democratic backsliding in Mexico, as is proven by many indicators, including V-DEM. However, at this point, a radical reversion to an autocratic regime, as it happened in Nicaragua or Venezuela, is not likely to happen, at least in the short term. In the worst-case scenario, AMLO’s attempts to erode Mexican democracy could lead to a regression to the old “revolutionary nationalism” style of the ’70s, and 80’s implemented by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, PRI, which ruled the country for 70 years and is the party where AMLO started his career as a politician. Revolutionary nationalism was a model of a single party, centralized in the Executive, who controlled the Congress, the Judiciary and influenced all sectors, public and private. During the second half of his mandate, AMLO will try to implement his whimsical policies but might not get too far. The “tropical Messiah” (Krauze, 2020) has found a barrier to his desires in some Mexican institutions and civic society. He will try, though, “even if they call me messianic, I am going to purify the country,” AMLO.

0 Comments